| AS-505/CSM-106/LM-4 |

F MISSION NCG 724

|

Under normal circumstances the crew of Apollo 10 would appear to be the team to land, but there were a number of reasons to make it the penultimate mission.

There had been some thought given to Stafford and Cernan landing, for instance George Mueller pushed for a landing, but he was known for his aggressive approach, as one colleague said, “He always shot from both hips.” A dress rehearsal mission had been planned since June 1967 and at that stage the mission wasn’t quite ready to support a landing.

There was still work to do on a number of different docking techniques as well as checking out communications and tracking capabilities at lunar distances. Not enough was known about the Moon’s environment for some of the manoeuvres, for example there were gravity peaks caused by heavy material under the moon’s surface called Mascons, which affected a spacecraft’s flight path; the lunar landing computer software wasn’t quite ready; and the LM was a shade overweight (it had been planned to use it for an Earth orbit flight test) which may have caused problems lifting off the lunar surface. So it was planned that the Apollo 10 LM would fly within 15,000 metres of the lunar surface, and sink into oblivion instead of celebrated world history.

The prime crew were Tom Stafford, John Young,

and Eugene Cernan – all space veterans from Gemini. Backing them

up were Gordon Cooper, Donn Eisele, and Edgar Mitchell.

|

Apollo 10 crew. Eugene Cernan, Tom Stafford, John Young. |

On 3 April at the top of the NASA tree Democrat Dr Thomas Paine took over from James Webb as the NASA Administrator and carried the responsibility of the first Moon landing. With President Nixon a Republican no one was quite sure how NASA would fare with this mix.

LAUNCH

|

|

Apollo 10 on the launch pad.

|

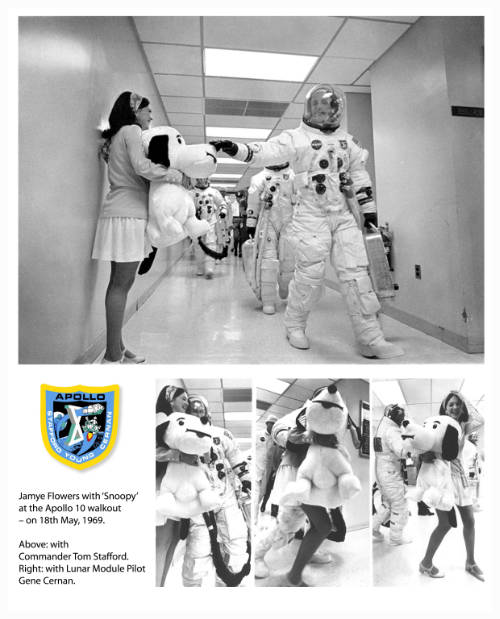

As the crew walk out to the transfer van, Gene Cernan’s secretary, Jamye Flowers holds a giant Snoopy doll. Tom Stafford pats Snoopy (top), while Gene Cernan attempts to take Jamye and Snoopy with them. (Collage: Colin Mackellar.) |

At 1249 USEDT on 18 May (0249 AEST 19 May) 1969 Apollo 10 left the Kennedy

Space Center’s Pad 39B and headed for the Moon on the second Earth orbit.

This was the only time that Pad 39B and firing room 3 were used for an Apollo

mission.

During the Trans Lunar Injection (TLI) burn the astronauts were suddenly shuddering to vibrations from the booster rocket pressure relief valves, and as their vision began to blur they all feared the mission was going to end before they had left the Earth. Stafford’s fingers reluctantly curled around the abort handle as he called Houston through gritted teeth: “Okay, we are getting a little bit of high frequency vibrations in the cabin.”

After five minutes of suspense the burn ended on time and they were safely on their way to the moon, later trying out the first colour television camera to be used on a lunar flight.

They went into Lunar orbit at 1645 EDT on 21 May (0645 AEST 22 May), to emerge on the other side full of the exciting views of the moon they were seeing:

Apollo 10: “Houston, Ten.”

Houston: “Go ahead, Ten.”

Apollo 10: “It’s amazing what you can see with earthshine on

the surface of the moon it seems to be very well lit from our altitude here.

The moon past the terminator is totally dark as long as we are in sunlight,

but the minute we go out of the sunlight into darkness ourselves, the moon

then glows right at us.”

Cernan: “The LM thrusters stick out like a sore thumb in earthshine,

but they don’t keep you from seeing any of the stars at night it’s

real well lit up.”

Stafford: “In earthshine you can see right into the craters, you can

see shadows in the craters from the earthshine. The more you become adapted

to it, it’s phenomenal the amount of detail you can see.”

Houston: “Roger Ten.”

|

| John Young holding a caricature of Snoopy for the camera during a telecast from space. Image: NASA. |

THE FLIGHT OF SNOOPY

There was some concern about an unusual twist of 3.5 degrees in the two spacecraft’s alignment while docked due to some holes that hadn’t been drilled. Would the latches holding the two spacecraft together be damaged by undocking? Mission Control didn’t want to take the risk so Flight Director Glynn Lunney went to George Low and was given the okay go ahead. Charlie Brown and Snoopy separated.

Stafford and Cernan were now in a spacecraft that could not

get them back onto the Earth. They were relying on the LM giving a faultless

performance and their being able to rendezvous and dock safely. What if something

went wrong on their return to Young, and they were unable to dock properly,

as nearly happened on Apollo 14? Unless they could transfer from the LM to

the CSM with an EVA, they would be stranded in lunar orbit, and Young would

have to return home alone.

|

|

The gleaming CSM Charlie Brown soaring over the Moon’s scarred surface. The S-Band steerable antenna we tracked is clearly visble. The pristine shine was soon wiped off by the fiery reentry. |

As Charlie Brown fell away Young called, “Adios, we’ll

see you back in about six hours,” and Cernan replied: “Have

a good time while we’re gone, baby.” Stafford added: “Yeah

– don’t get lonesome out there, John.”

They fired Snoopy’s rocket to drop down to within 15,240 metres of the Sea of Tranquillity. Looking down from high above Young reported, “They are ramblin’ among the boulders.”

As they made their first pass over the southwestern corner of the Sea of Tranquillity an excited Cernan called out: “I’m tell you, we are low. We’re close baby!... we is down among ’em, Charlie.”

Capcom Charlie Duke responded, “I hear you weaving

your way up the freeway.”

Snoopy raced across the face of the planned prime Apollo 11 landing site

at just under 6,000 kilometres per hour, Stafford giving a running commentary

on the features he could see out the window and trying to take pictures with

a faulty Hasselblad camera. They checked the computers, landing radar, and

kept an eye open for any unexpected surprises.

They then looped back out to return for the second pass when they planned to simulate a launch above the landing point by firing the ascent stage rocket to separate from the descent stage and return to Charlie Brown.

As Stafford brought the Lunar Module down for the second pass

he spoke to Houston, “Okay, we are coming up over the site. There’s

plenty of holes there. The surface is actually very smooth, like a very wet

clay... with the exception of the very big craters.”

|

|

One of Apollo 10’s views of the Apollo 11 Tranquillity Base landing site. |

SNOOPY GOES BESERK

At 1932 USCDT (1032 AEST) they were preparing to stage, to drop the descent part of the LM off, when without any warning, the two astronauts found themselves spinning around out of control as Snoopy began to jerk and buck about like a wild horse.

Acutely aware of the menacing terrain racing past their windows, with mountains

grinning at them like gigantic decayed teeth (as Cernan described it), Stafford

took over manual control and Snoopy promptly quietened down. The wild gyrations were caused by a switch

in the navigation system set incorrectly.

The LM had two computers; the Primary Navigation Guidance System (PNGS pronounced “Pings”) for indicating where they were, and the Abort Guidance System (AGS) for use near the Moon in an emergency launch. During the checks Cernan had correctly switched from PNGS to AGS, then unaware the switch had already been operated Stafford had switched it back to PNGS so instead of keeping Snoopy on a steady course, the system lost control looking for Charlie Brown that wasn’t there.

To add to the confusion Stafford then threw the switch back to AGS thinking it was going to PNGS.

During all these fast moving events there were communications problems. Not

keeping an eye on where the LM was spacecraft antennas were not always pointed

for optimum signal, and the astronauts had difficulty in communicating, as

well as telemetry and ranging were unreliable at times.

Ten minutes later the ascent engine fired to push them back up into orbit to meet Young in Charlie Brown. At 2300 (1400 AEST) they met, and Mission Control broke out a large cartoon showing Snoopy kissing Charlie Brown, saying, “You’re right on target, Charlie Brown,” and a little later Snoopy’s engine was fired again for a test before it was cast off.

After 31 orbits Apollo 10 and its crew left the moon, sending TV pictures

of it back to Earth. On Sunday, during TEC, when the astronauts woke up they

switched to down voice and played a tape of ‘Come Fly with Me’ and

whistled to it, then pretended to be a breakfast announcer on a radio station.

Then John Young observed that as they were rolling in the PTC (barbeque) mode

at 3 revs per hour they were experiencing three days per Earth hour so their

spacecraft calendar now put them in the middle of August!

|

|

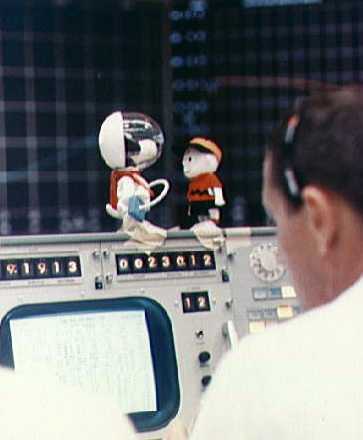

During Apollo 10 Charlie Brown and Snoopy rode the consoles in Mission Control. Capcom Charlie Duke at right. |

THE FASTEST HUMANS IN HISTORY

With extra fuel left over from the lunar activities they burnt

it off to accelerate the spacecraft back to Earth at a record 39,897 kilometres

per hour, making the crew of Apollo 10 the fastest humans in history.

At 1152:23 USCDT on Monday 26 May (0352:23 AEST 27 May), after a mission elapsed

time of 192h 3m 23s they splashed down into the Pacific 635 kilometres east

of Pago Pago, 5 kilometres from the recovery carrier USS Princeton.

The crew aboard the carrier were treated to a spectacular sight of the Service

Module streaking across the pre-dawn sky in a blazing fireball as it burned

up, followed by the Command Module silhouetted against the brightening sky

under its three big parachutes. Waiting beneath, the recovery helicopters

buzzed about with their flashing running lights stabbing the dark velvet blue

sky. When the astronauts in the rubber-ducky looked up at the helicopter hovering

above they saw “Hello there Charlie Brown” written across the underside

of the fuselage.

|

Back on Earth in the colourful dawn off Pago Pago

the USS |

At Honeysuckle Creek we were now familiar with the lunar missions and the

ground procedures and had moulded into an efficient team.

We were ready to

support Apollo 11 for an attempt at landing on the Moon.

The Apollo 10 mission patch was preserved and scanned by Hamish Lindsay.