11–22

October 1968

by

Hamish Lindsay

| AS205/CSM-101 |

MISSION C |

NCG 717 |

|

|

The

Apollo 7 crew:

Donn Eisele, Wally Schirra, Walter Cunningham.

NASA Photo: S68-33744.

|

Commander : Wally Schirra

CSM Pilot : Donn Eisele

LM Pilot : Walter Cunningham

The Apollo 7 was the first Apollo manned mission,

flown to check out the new Apollo launch systems, the Command Module and its

ability to fly in space, navigation and rendezvous procedures with a host

of lesser tests.

Apollo 7 was Honeysuckle’s (and the tracking network’s)

first taste of manned Apollo flights. It was not very exciting on the ground

– for me it was just a continuation of the Carnarvon Gemini flights –

grabs of signals for up to 12 minutes every 90 minutes as the spacecraft orbits

the Earth while the crew evaluated the Apollo spacecraft for manned flight.

At Honeysuckle Creek we had a quick visit from Goddard’s

NASA 421 Sim Team led by Jim Kennedy on 2 Tuesday July 1968 to check us out.

However the aircraft only flew for us on 5 Friday and 6 Saturday July.

The crew selected by Deke Slayton were Wally Schirra,

Commander; Donn Eisele, Command Module Pilot and Walter Cunningham,

Lunar Module Pilot (with no LM). The back-up team were Tom Stafford, John

Young, and Eugene Cernan.

Cunningham:

“The first Apollo mission was originally scheduled

to be flown by Gus Grissom and his crew two years earlier in the first manned

spacecraft ever built by the Rockwell Corporation. At that time Wally was

planning to leave the space program for a job in private industry. Only

a personal appeal by his old friend and good neighbour, Gus (Grissom), convinced

Wally to stay on as his back-up. While Wally never got excited about playing

second fiddle to anyone, Donn and I were overjoyed just to be ON a back-up

crew – any back-up crew. And we certainly never expected to actually

fly the first mission.

A few short months later we lost our three close friends

in a spacecraft fire on the launch pad and inherited their key mission –

the first giant step towards landing a man on the moon. With a new motivation

and challenge in front of him, Wally committed another two years to the

job.”

Schirra, son of a WWI fighter ace and a barnstorming,

aerial wing-walking mother, was a cool and professional pilot. He was 45 years

old and the oldest astronaut to enter space at the time. He was the only astronaut

to fly all three Projects – Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, while both Eisele

and Cunningham were first timers. Schirra had already handed in his resignation

from NASA two weeks before the mission, saying he wanted to quit while he

was ahead, and he wanted it to be clear that he was single-minded about the

Apollo 7 mission – that he cared for nothing else. He reckoned he had

matured over the years and was no longer the boy in scarf and goggles, the

jolly Wally of space age lore. So anything he did would not jeopardise his

career.

After the death of his three friends in the Apollo 1

fire, he took a good hard look at where the space program was headed. Before

the investigation into the fire had ended he took his crew, the back-up crew

and all the support crew to a borrowed house in Miami. To get their minds

off the fatal accident they cut all communication with the outside world and

conducted intense training sessions to fit their responsibilities into the

upcoming schedule. He decided then that he wasn’t going to be influenced

by extraneous scientific and political interests. He would not tolerate anything

or anyone that would affect the safety of the mission or the crew.

He became a new Schirra. Chris Kraft described him as

raising hell, bitching and hollering about everything. For instance he was

told there would be no coffee on the ship. “You’re asking a Navy

guy to give up coffee,” he exploded and fought all the way to the top

to have coffee included in the stores. At one top brass conference in Houston,

during the break the refreshment trolley was wheeled in without any coffee.

In response to the outrage he got up and said, “Gentlemen, since you

deem it inappropriate for the crew of Apollo 7 to drink coffee during the

mission, I thought you might try doing without it for just one day.”

He won his point.

Apollo 7 was a trial Block II Command Module which had

the capability to accommodate the Lunar Module, but did not have docking facilities,

or the transfer tunnel to the Lunar Module, as there was no LM. Schirra wanted

to call his spacecraft Phoenix but NASA declined.

Schirra voiced his concern about the weather at launch.

As this was the first time men were going to ride a Saturn rocket into space,

there was a chance it might have to be aborted during the launch phase. Tests

had shown that to land on hard ground with the early Block I couches they

would be using would almost certainly injure the occupants, so Schirra insisted

that one of the launch rules should be a maximum onshore breeze of 18 knots,

so they could land with the parachutes in water if they had to abort.

Launch

On launch day, 11 October 1968, a high-pressure system

over Nova Scotia created an easterly wind varying between 20 and 25 knots

– blowing straight inland. The temperature was 28.3°C and relative

humidity 65% with cumulonimbus clouds with a base at 2,100 feet. Over in Houston

Gene Kranz’s team began the countdown, checking out the mission control

center, and handed over to Gerry Griffin’s gang to check out the spacecraft.

Glynn Lunney’s flight controllers handled the day shift for the actual

launch.

At 2235 AEST the crew crawled into the spacecraft two

and a half hours before launch while at Honeysuckle Creek we were busy with

Site Readiness Tests, preparing for the first glimpse

of the spacecraft. We were listening to the progress of the countdown on an

intercomm channel which didn’t tell us much.

By Schirra’s rule the launch should have been postponed,

but they decided to go, and the Saturn IB, a scaled down Saturn V, thundered

into the air at 1102:45 USEDT 11 October 1968 (0102:45 AEST 12 October) from

Pad 34. Schirra described the launch as “… a sense of elation when

the bolts blow, the hold-downs release and the big maumoo leaves the launch

pad.” But the elation of lift-off was tempered with anger at his safety

rule being broken. He felt better as they progressed safely through the abort

stages, the Saturn giving a smoother ride than he had experienced in either

the Mercury or Gemini flights. The Saturn IB was a much smoother ride than

the bigger and more powerful Saturn V.

|

|

The launch of the Apollo 7 Saturn IB.

From an Apollo Archive scan.

|

Cunningham described his experience of his first and

last launch,

“The (Saturn IB) rocket rises from the pad so

slowly, so ponderously at first, that you could be imagining it even moved

at all. It is an agonizingly slow ten seconds before Apollo 7 clears the

tower. One million three hundred thousand pounds is balancing on an arrow

of flame. Painstakingly, it climbs, trailing a fireball as vivid as the

colours of hell. At the spectator bleachers, two-and-one-half miles away,

the earth actually trembles. The vibrations, the noise, the shock; they

roll over you in waves. And, from out of the second fire on Pad 34 rises

our modern-day Phoenix.

I’d seen many lift-offs, but this one was different:

It was the largest rocket ever launched carrying the largest payload ever

placed in orbit. And, oh yeah, this time I was riding inside, not watching.

In the cabin we have no way of sensing the actual moment

of lift-off. We know our Phoenix has begun its climb from out of the fireball

only because the spacecraft clock begins ticking off the elapsed time and

Wally can see the altimeter climbing. Inert metal and fuel has turned into

a live monster. Once quiet dials begin to move and jump. Donn has the G

& N (Guidance & Navigation) computer flashing our trajectory parameters.

I am monitoring the environmental and electrical systems to ensure that

the cabin pressure is bleeding down according to schedule to prevent a blowup

in the vacuum of space. It is the most complex machine ever built by man

to be operated by man. And our job is to see that the monster does not eat

us alive.

A few seconds after lift-off, we roll a few degrees

to enable a pure pitch manoeuvre to eventually place us in the correct orbit.

We continue to pitch over backwards (much like going over the top when doing

a loop), which will take us into orbit upside down and heading East.

For the first two minutes and forty-seven seconds,

our only visual contact with the outside world is through a small forward

viewing window on Wally’s side and a small round porthole over Donn’s head.

At that point, when we jettison the launch escape tower, it carries the

boost protective cover with it and all five windows are exposed for the

first time. However, there is nothing to see but sky until the last few

minutes before reaching orbit. Donn started rubbernecking right after the

cover cleared, and we both snapped at him to keep his eyes inside and his

mind on the job.

Apollo 7 was fifty miles high and sixty miles down-range

when the word came from Houston, “Seven, you’re looking good.”

For the first ten minutes and thirty seconds

of a nominal launch, except for performing a few essential functions, we are

mostly along for the ride. We’re space pilots, but we aren’t flying the spacecraft.

And Mission Control doesn’t control it. It is an on-board computer operation

all the way into orbit. We’re on automatic pilot. The flight path has

been programmed. We monitor the instruments – as does Houston –

to see how good a job Seven is doing flying itself. If it doesn’t perform,

we can take over, fix it or get off.”

In deference to the Apollo 1 fire, when the cabin was

filled with pure oxygen, the cabin atmosphere at launch was 65% oxygen and

35% nitrogen (though the suits had pure oxygen) but was purged to 100% oxygen

for the rest of the mission at a pressure of 34.5 kPa.

Apollo 7 entered Earth orbit at 0113:11 AEST 12 October

and took up an initial orbit of 227.8 by 282.1 kilometres with an orbital

period of 89.5 minutes and a speed of 28,015 kilometres per hour.

Eighty minutes after launch, disaster struck at Mission

Control. A power failure plunged the busy room into semi-darkness and blacked

out all the consoles. Flight controllers stared helplessly at blank screens

and dead displays with only the emergency lights for their eyes to focus on.

Power was restored within two minutes and the mission continued with no interruption

as far as we were concerned.

The crew spent the first day test firing the SPS (Service

Propulsion System) engine, beginning at 0327:40 AEST, and practising rendezvous

manoeuvres with the SIVB. The SPS was the largest engine to be manually thrust

vector controlled. When they first experienced the boost from it, pressing

them into their couches, Schirra involuntarily whooped “Yabbadabbadoo”

Eisele felt: “It was a real boot in the rear. We got more than we expected.”

Eight firings resulted in eight almost perfect burns

to prove beyond doubt the engine was reliable. It had to be, because this

was the engine to put the spacecraft in and out of lunar orbit in the upcoming

missions.

|

|

The Saturn IVB stage during docking manoeuvres

over the Gulf of California.

ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed Hengeveld.

|

|

|

The Saturn IVB stage during docking manoeuvres

over New Orleans.

The white disc is a simulated docking target.

ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed Hengeveld.

|

Illness

Then: “Surprise! On our second day in orbit, Wally

Schirra woke up with the Grand Daddy of all head colds – hardly a fair

reward for the three hours of sleep we had enjoyed following a launch day

that was 23 hours long. Fair or not, it quickly turned our cosy little spacecraft

into a used Kleenex container,” Cunningham said.

Schirra called down to mission control to say he was

thinking of taking an antibiotic or decongestant, but the surgeon on duty

recommended only a decongestant. This was the first illness in space in the

American space program.

Cunningham,

“Wally’s cold was a consequence of a bird

hunting trip we made three days before launch that ended up in a cold rain.

The cold left Wally feeling too wretched for several days to even get out

of his sleep restraint. On Earth, he might have called in sick and gone

to the doctor. In the spacecraft, that luxury was not available and Wally’s

discomfort was magnified by the unrelenting demand to perform one complex

test after another. The spacecraft commander played a key role in many of

the tests and he continued to perform, even from his ‘sickbed’.

Wally’s discomfort, added to a full schedule of activities, made him

more irascible by the day. He knew if the mission had to be aborted before

he was completely well, his eardrums would probably be damaged from the

pressure change during re-entry.

Most of the crucial activities during those times when

our necks were on the line were Wally’s, and that responsibility carried

with it the lion’s share of the stress. A stupid mistake by any of

us could blow the mission, or worse – the spacecraft. But it was Wally’s

hand on the abort handle during boost; he did most of the spacecraft manoeuvring;

and he flew the re-entry. It was on those activities where he concentrated

his training. He was the Captain of our ship but sometimes that mantle didn’t

rest lightly on his shoulders.”

A common head cold in space is bad news as mucus accumulates

in the nasal passages and does not drain out of the head. Schirra tried blowing

hard into tissues but found it only made the eardrums uncomfortably painful.

|

|

Wally Schirra

looking rather haggard on 14 October 1968.

From an ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed

Hengeveld.

|

Cunningham,

“By the third day Wally was miserable. In our

on-board storage we had included a large supply of vacuum-packed tissues.

They were useful for wiping off the grime, catching urine drops, or any

other of the many required body ablutions. Fortunately, we had overstocked

on this item. However, the used ones were not vacuum-packed and, consequently,

took up twice as much space.

As soon as we were squared away in orbit, Wally began

blowing his nose, and within a short time we were stuffing used tissues

in every empty spot we could find. Wally showed no interest in conserving

them, and Donn and I began to worry whether a tissue crisis could end the

mission. When we suggested to Wally that he might try to get more than one

blow out of each tissue, our pleas fell on deaf ears.

There was no doubt that Wally felt he had caught the

cold they were saving for Judas. He was sleeping poorly and becoming as

jumpy as a frog in a biology lab. He continued to perform, issuing orders

from his ‘sickbed,’ but the heavy workload at the outset of the

mission, combined with his discomfort, made Wally more irascible by the

day. He didn’t miss an opportunity to nail Mission Control to the wall,

and wanted the ground to believe our spacecraft was a hospital room. Donn

and I were amazed at the patience of those in the control center with some

of the outbursts that came their way. On the ground they were well aware

that every word of the air-to-ground communications was being fed directly

to the press center, a fact of which we had not been informed. So Wally’s

bad temper was making big news back home.”

Later Eisele developed a runny nose giving an impression

that the entire spacecraft was rife with colds, but according to Cunningham

only Wally had a real problem. Eisele’s symptoms did not develop, and

Cunningham never suffered any affliction at all.

|

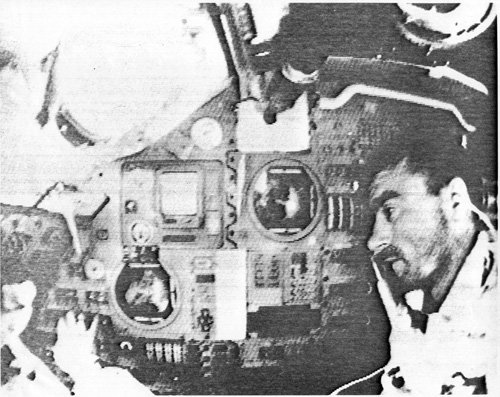

|

Donn Eisele during the mission.

From an ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed

Hengeveld.

|

Once the mission settled down, for us each tracking period

began as a brief pass in the north east, each pass increasing in duration

until the spacecraft crossed overhead with maximum duration of around 11 minutes

then the passes shortened as the spacecraft worked its way out of sight into

the north west. The first and last passes might only be a minute. It meant

we had endless H-30 countdowns (30 minutes to the spacecraft Acquisition of

Signal) every 90 minutes, except when the spacecraft went out of sight for

a few hours, when the astronauts usually had their sleep periods. During this

period their orbit took them over China and South America, well out of our

range. This monotonous routine went on for the whole mission.

With Schirra’s irritability, angry at his launch

rules being broken, and suffering the head cold in the confined cabin of the

spacecraft, he became decidedly difficult with mission control when they wanted

to change the flight plan. When the Houston flight controllers tossed some

changes into the schedule, Schirra showed his annoyance. He had always opposed

the television system being installed on his flight – he saw this flight

as an exercise to check out the new procedures and a new spacecraft, a spacecraft

that had just incinerated three of his good friends (Grissom was one of the

Mercury Seven and his next door neighbour). As far as he was concerned entertaining

television was an unwelcome distraction from the business of a test pilot’s

duties evaluating a new, untried spacecraft, but had to relent when the heavy

guns were brought in to force the issue. Chris Kraft insisted that the American

public should get the opportunity to see the action through live video broadcasts.

When Schirra woke from a sleep on Saturday morning in

the spacecraft he heard Eisele arguing with Houston about a television transmission

the ground wanted later in the day. Remembering he had not checked the system

out he decided not to support it. Houston was aghast – astronauts don’t

go against orders from Mission Control. The boss of the astronauts, Deke Slayton

admitted, “There was nothing I could say or do to get Wally to change

his mind.” He had tried.

Slayton: “Apollo 7, this is Capcom Number One.”

Schirra: “Roger.”

Slayton: “All we have agreed to do on this is flip

it. Apollo 7, all we have agreed to do on this particular pass is to flip,

flip the switch on. No other activity associated with the TV. I think we are

still obliged to do that.”

Schirra snapped back: “We do not have the equipment

out, we have not had an opportunity to follow setting, we have not eaten at

this point, I still have a cold, and I refuse to foul up our timelines this

way.”

This was mutiny, and from this point the mission became

an uncomfortable confrontation between the flight controllers on the ground

and the spacecraft crew, Eisele and Cunningham throwing their lot behind their

skipper. Cunningham felt that Schirra was justified in the television case.

Eventually, from 0045 AEST 15 October, the first “Wally,

Walt and Donn Show” was aired, repeated each USA morning as the spacecraft

passed over the Corpus Christi and Cape Kennedy tracking stations, the only

two stations equipped to pass on the live transmissions.

|

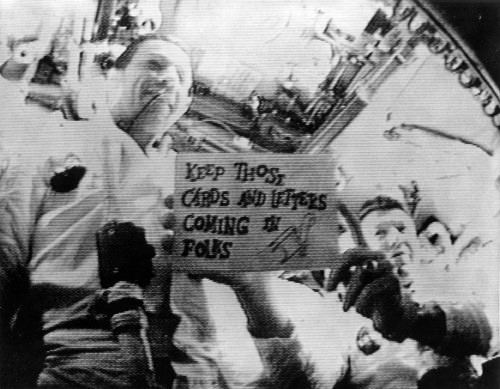

|

Donn Eisele

(left) and Wally Schirra on nationwide

television on 14 October.

(“Keep those cards and letters coming in” is a quote from

Dean Martin’s weekly television programme.)

Image: NASA Photo ID: S68-50713, courtesy Dick Nafzger.

|

Funnily enough the mission rules laid down by the hierarchy

had thought of every conceivable emergency except dealing with disobedient

astronauts!

Cunningham,

“My own attitude was cautious, if not downright

cowardly. I did not participate in, nor did I believe the poor behaviour

and air-to-ground abuse was justified. I also realised that all three of

us would be tarred by the same brush. So when the exchanges became heated,

or threatened to, I would disengage myself, stay out, and later play the

apologist for mission control’s position. It was awkward and difficult for

someone not known for his diplomacy. The new tests were sometimes poorly

thought out and did add to our workload (which was not overloaded), but

they also produced valuable data.

In the end, the mission left a bitter residue with

the support people and controllers who had worked with so many crews before.

In Glynn Lunney we had perhaps the best flight director the Johnson Space

Center ever produced, and his patience was tried to the limits. The technical

success we achieved on the mission was blemished to a great degree by the

reputation we earned for being difficult. Then, too, our mission objectives

were accomplished so routinely that the news media had very little to report

except those ‘human interest’ items.

In retrospect, at least four factors combined to make

the flight a pressure cooker for Wally Schirra: his age (he was forty-five

at the time); his pre-flight lack of interest in the details of many of

the test objectives; the nuisance of his head cold, the effects of which

were heightened by zero gravity; and the long duration of the mission. His

longest previous stay in space had been twenty-five hours, and Wally was

noted more for his quick style and grace than for his endurance.

When one considers the strange sleeping and eating

cycles we endured, and the closeness of our quarters, it’s remarkable

that more tensions didn’t result. On our first day in space we were

up for twenty-three hours straight before getting to sleep. NASA liked to

get its money’s worth from every crew – and did, especially at

the beginning of missions.”

Schirra found the much bigger, sluggish Apollo Command

Module a very different proposition to the more ‘sporty’ Gemini

spacecraft. The crew practiced a rendezvous with the Saturn IVB but without

the rendezvous radar to provide the range and approach velocity they had an

anxious time judging the braking and distance away to begin station keeping

alongside the Saturn IVB at 0658 AEST 13 October, so kept a safe 30 metres

away from the tumbling rocket for the 25 minute exercise.

When the crew did turn the television equipment on Schirra

was all charm and the Wally, Walt and Donn shows broadcast live over the American

networks were so popular they won a special Emmy award. It was a new experience

for Earthlings to see astronauts tumbling around weightless, even if it was

on a screen.

|

|

Donn Eisele (left) and Walt Cunningham

during the third TV broadcast.

Scan: Colin Mackellar. Image courtesy Bruce Withey.

(Other SS-TV images here.)

|

Cunningham,

“Normally, no one slept his entire period; I was

invariably up before it was time. After a couple of problems developed while

Donn was on watch, Wally and I began to sleep with one eye open.

Sixty-one hours into the mission, while Donn was on

watch, we had a malfunction in the electric power system that threatened

a complete electrical shutdown. Wally and I were supposed to be sleeping,

but I was so near to consciousness beneath my couch that I was able to rouse

myself and correct the situation before Donn could get involved. The electric

power system was my specialty. A day or two later, Wally and I each awoke

at different times to find Donn asleep during his watch. We found him floating

asleep up in the docking tunnel, in the zero-g foetal position: legs, back,

and arms all slightly bent. It was not the best way to watch over the spacecraft.

On later missions it became standard practice for all three crewmen to sleep

simultaneously, so in retrospect it wasn’t critical. But on this first

mission it didn’t make Wally and me feel very secure, knowing the spacecraft

was brand-new and unforeseen problems could arise at any moment.”

By day four the astronauts were already finding the endless

orbits around the Earth were becoming monotonous. Schirra commented, “We

were on day four when I realised that 10.8 days is an eternity.” The

endless sunrises and sunsets each 90 minutes became boring. With no books

to read or tapes to play to pass the time they made up simple games such as

trying to throw a pencil through a ring made by a thumb and forefinger. As

the pencil always began to tumble they never succeeded.

When getting dressed one day Schirra noted that men on

the Earth pull their trousers on one leg at time, but he found with weightlessness

he was able to pull both legs on simultaneously.

During day 8 Houston had instructed them to track a planet

down to the horizon. Their telescope was combined with a computer and sextant.

Unfortunately when the computer went into the ‘tilt’ mode it would

lock up. Following this exercise the computer went into the tilt mode and

locked up. “What idiot sent that command,” growled Eisele. Without

the computer they were effectively shut down, no more manoeuvres in orbit,

no guided reentry and all the work they had done was invalidated. “Hey,

remember the night we were trying to look at the nurses?” Eisele called

out. Luckily he had come across this problem when they were trying the equipment

at the MIT lab and were observing some nurses across the way for fun and a

passing instructor told him to press clear and add together

to clear the problem. Eisele tried and it worked.

|

|

Walt Cunningham during the mission.

From an ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed

Hengeveld.

See also this

picture taken near the end of the mission, on Day 9.

|

Cunningham,

“Halfway through the flight we had

already accomplished more than 75 percent of our objectives – missions

were always front-end loaded – and, rather than exult in the days, we

began to just check them off. The flight plan dictated when the day ended.

When it said, ‘sleep’, the day was over. But the start of our sleep

periods were moved around the clock, from 5:00 am on the first day (really,

the morning of the second day), to 5:00 pm on the tenth day. (We continued

to reference our on board time to the Cape, where we had spent our last several

weeks and would return after splashdown.) At the end of each day we would

scratch a mark through the date on the calendar. But by October 17, the seventh

day, Wally was counting the days so anxiously that he began crossing them

off soon after we finished breakfast. There is no question; we were beginning

to anticipate that eleventh – and final – day.”

In the crew wake-up on his final shift of the mission,

as a joke to stir the crew, Flight Director Gerry Griffin threatened to keep

Apollo 7 aloft for another four days, to beat the Gemini VII record of fourteen

days, but was howled down.

|

|

During Rev 91 on 17 October 1968

coasting along in the calm of space

Apollo 7 passed over Hurricane Gladys trashing the Gulf of Mexico.

NASA image AS07-07-1877

|

Several days before the mission ended, they began to

worry about wearing their suit helmets during reentry, which would prevent

them from blowing their noses. It was feared the build-up of pressure to the

Earth’s atmosphere might burst their eardrums, so they were told to hold

their noses, close their mouths and try to blow through their Eustachian tubes

to keep the pressure in the middle ear in balance with the increasing air

pressure. To do this Schirra told his crew that they would make the reentry

without their helmets on. Slayton, in mission control, tried to persuade them

to wear the helmets to follow mission rules, but Schirra would not give in

as he felt he was ultimately responsible as commander on the flight.

They each took a decongestant pill about an hour before

reentry and made it through the acceleration zone without any problems with

their ears.

|

|

During Rev 134 they came upon the morning sun

blazing down on a more peaceful Gulf of Mexico on 20 October 1968

after Hurricane Gladys had moved on.

From an ApolloArchive.com scan processed by Ed

Hengeveld.

|

An 11.9 second de-orbit burn over Hawaii during the 163rd

orbit at 2042 AEST on 22 October was followed by splashdown at 2111:48, 370

kilometres south east of the island of Bermuda. Light rain showers were passing

by, with a 16 knot westerly breeze raising a one metre chop.

The temperature was a comfortable 23°C. The mission

took 260 hours 9 minutes 3 seconds (or 10 days 20 hours 4 minutes) to travel

a distance of 7,322,515 kilometres.

The Apollo flotation bags had their first try-out when

the spacecraft splashed down less than 2 kilometres from the carrier Essex

and promptly flipped upside down in the choppy sea. As soon as the bags righted

the spacecraft the helicopters were able to home in on the beacon signals.

|

|

|

Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and

Walt Cunningham onboard the USS Essex. |

I have spoken to both Chris Kraft and Gene Kranz, neither

of whom ever spoke to Schirra about his behaviour during the flight, and both

are not sure why he carried on the way he did. Chris Kraft’s comments

to me were,

“Schirra was recalcitrant – the whole crew was recalcitrant

as a result, and I imagine there was some justification for that on the basis

of what happened on the pad when we killed three people. As fliers they performed

the flight well – they just gave us a hard time on the ground.”

Gene Kranz answered my question with,

“This mission

was a spectacularly successful test of the manned maiden voyage of the Apollo

Command and Service Module. However, learning to work with Wally in flight

– well, in my book I called him the ‘grumpy commander.’ Unfortunately,

he got this cold in flight, and space is not too tolerant to people who end

up with a lot of congestion. It’s very difficult to sleep and continue

working – I guess he had his hands full. I never quite figured out why

Wally had such a burr under his saddle there.”

I could never get hold of Schirra himself, but I think

I have explained the reason for his behaviour from the printed material available.

Thanks to Schirra’s behaviour, neither Eisele or Cunningham ever flew

in space again. However, in his book “Flight,” Chris Kraft did admit

he would have given Cunningham another chance, however Walt resigned before

that could happen.

All the mission objectives were met and all the spacecraft

systems worked satisfactorily. The fuel cells providing electricity also supplied

hot water at 68°C for Schirra’s coffee. For the first time a live

television program was broadcast around the commercial networks from space.

Apollo Program Director Sam Phillips announced, “We achieved 101% of

our objectives.”

With a successful flight the Apollo Project was ready

to go. President Kennedy’s deadline of 1969 for a Moon landing now seemed

within reach.

|

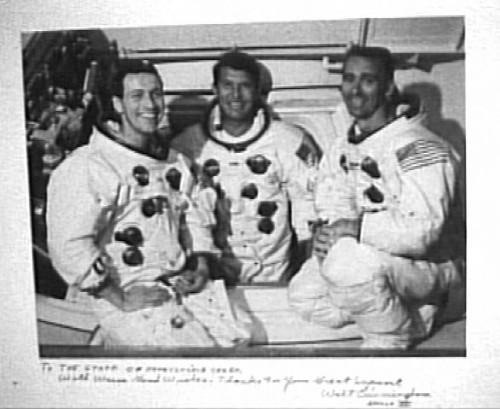

|

This photo of the crew was sent to Honeysuckle

Creek by Walt Cunningham.

In part, it reads, “Thanks for your great support.”

The picture was spied on the wall at Honeysuckle –

in some news film taken

on July 21, 1969, the day of the Apollo 11 landing (Australian time).

|

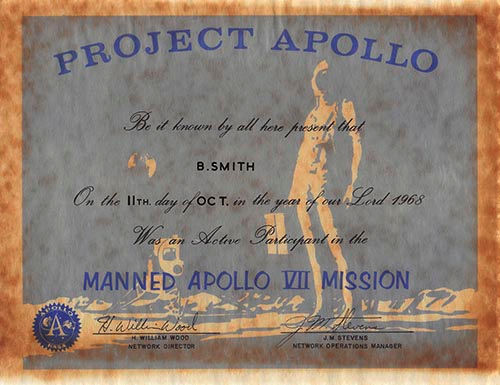

|

This certificate was presented to members of the Manned Space Flight Network – signed by H. William Wood, Network Director, and Mike Stevens, Network Operations Manager.

This copy was received by Honeysuckle’s Bernard Smith.

|

Text by Hamish Lindsay, formatting and processing of illustrations by Colin

Mackellar.

Apollo 7 mission patch scanned by Hamish Lindsay.