A visit to Island Lagoon

Australian author Ivan Southall visited Island Lagoon for his book, “Woomera”, published in 1962.

This is how he describes arriving at the station –

“An arm of Island Lagoon is the scene for Apollo and for the unmanned deep space programmes at present associated with it, Mariner and Ranger. It is the third of the satellite-tracking stations based within a few miles of Woomera village and lies in the opposite direction to our recent travels. Island Lagoon is down south, below the transcontinental line, seventeen road miles from the village square, and surely must be one of the queerest regions on the face of the earth, a vast salt-pan, larger than many of the great lakes of the world, a wasteland, usually as dry and as brittle as clinker. I elected to walk into it. I felt compelled to get out of the car and take my time, and that short walk carried me through one of the weirdest hours of my life.

The station manager, Bill Mettyear, dropped me a couple of miles short, indicated the general direction across country, and drove on down the winding road into the glaring depression. The silence was incredible, so deep that it sang in the ear-drums. There was no apparent life or movement. There was nothing except an immense sky of deep blue, intense heat, a deep foreground of undulating and fragmented red rock, and a glimpse of dazzling salt beyond. I could see the lagoon shimmering against a low, jet-black horizon, an extraordinary horizon. The lagoon was a thin white line of salt and clay with twin hills, a mile or so apart, rearing from its midst.

It was a disturbing place, tense with aeons of unwritten history, remarkable for itself, doubly remarkable because its unearthly beauty was a backdrop to modern man’s journeys to the planets. …

The Deep Space Instrumentation Facility lay somewhere in the east, and this took me over the strangest surface I have set foot on. All gibber clatters, but this was loose and shifting, sometimes fragmented, so hard and so sharp it cut my shoes. The earth seemed to have shed a skin. The skin had been cooked, and had flaked off like sunburn, and had splintered, and beneath it another skin had been cooked, flaked, and splintered. All seemed to have been destroyed by heat. I couldn’t ignore the thought that perhaps the surface of other lands might be like this in a hundred years or a thousand years after a thermo-nuclear war. It clattered and clanked, and the unearthly landscape heightened every uneasy sensibility.

The land looked naked, sterile – but it wasn’t. In places were the droppings of kangaroos and pastel smudges of plant life. From a distance of a few steps, all, except the few saltbush, seemed to be lichens, but all were not lichens. Many were tiny plants, an inch or two high, surviving on rock. There were trees occasionally here and there, warped and twisted and stunted by starvation, trees two feet or less in height, but probably older than I was. …

I wandered on into the east, downhill, and there it was, seemingly a long way off, the great dish of the radio telescope, designed for the express purpose of tracking instrument packages and manned spaceships and receiving messages from them during their journeys to distant worlds.

I almost had to pinch myself. This was honest-to-goodness truth, an accomplished fact, an everyday sight for a handful of flesh-and-blood scientists, engineers, and technicians. And they had placed it here, in this extraordinary country, this moonscape, undoubtedly aware of its dramatic impact.

The dish was like a huge inverted parasol, 85 feet across, 120 feet high, dwarfing the buildings at its base. Around it was bare red earth, and beyond it was the shimmering brilliance of Island Lagoon, stark against the gaping depths of the sky.

DSS-41, Island Lagoon, c. 1963.

With thanks to Don Gray. Scan: Colin Mackellar.

It was overpowering, and probably I was a little too closely tuned emotionally to the challenge posed by deep space to stick to the mechanics of the business. That seemed to be my frame of mind throughout most of that day, and I still see it and feel it as awe-inspiring. Later when I tried to climb the antenna to cross the rim of the great dish, I was unable to do so. Two-thirds of the way up I was so overcome by the criss-cross confusion of girders around me and the extraordinary landscape beyond that I couldn’t grope another step, and even doubted my ability to get down again.”

– extracted from Woomera, by Ivan Southall, © Angus and Robertson Ltd., 1962, pages 227–229.

|

Photo of Ivan Southall – copyright unknown.

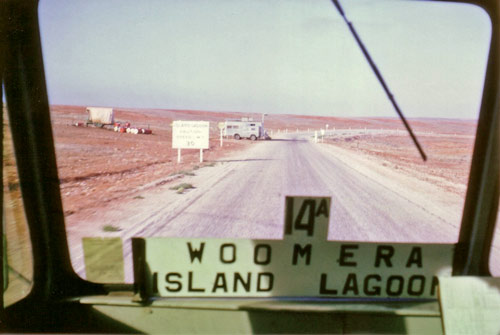

Arriving for work at Island Lagoon. The trailer you can see in the distance is by the security gate for entry to Island Lagoon. A lonely job for the security man.” Photo: Pat Delgado. |